The thread has been lost; the labyrinth has been lost also. Now, we no longer even know whether these corridors that encircle us are those of a labyrinth, a secret cosmos, or a chaos of pure chance. Our beautiful duty is to imagine that there exists a labyrinth and a thread. We might never come across the thread; or we might stumble upon it unexpectedly and then lose it again in an act of faith, in the rhythm of a line, in a dream, in the sort of words that are called philosophy or in a moment of mere and simple happiness. Jorge Luis Borges. The Thread of the Fable.Cnossos, 1984

Legend has it that the Moirai –also known as Fates- govern the thread of life of every mortal from birth to death.Daughters of the night, they patiently and always in the darkweave our destiny. Controlling our fate –our past, present and future- they are invisible. Something similar happens with Arachne. Turned into spider, her wonderfulwebs are condemned to be transparent.

This condition of invisibility associated with women and manual work seems to reaffirm the patriarchal notions that still today confine female work to anonymity.

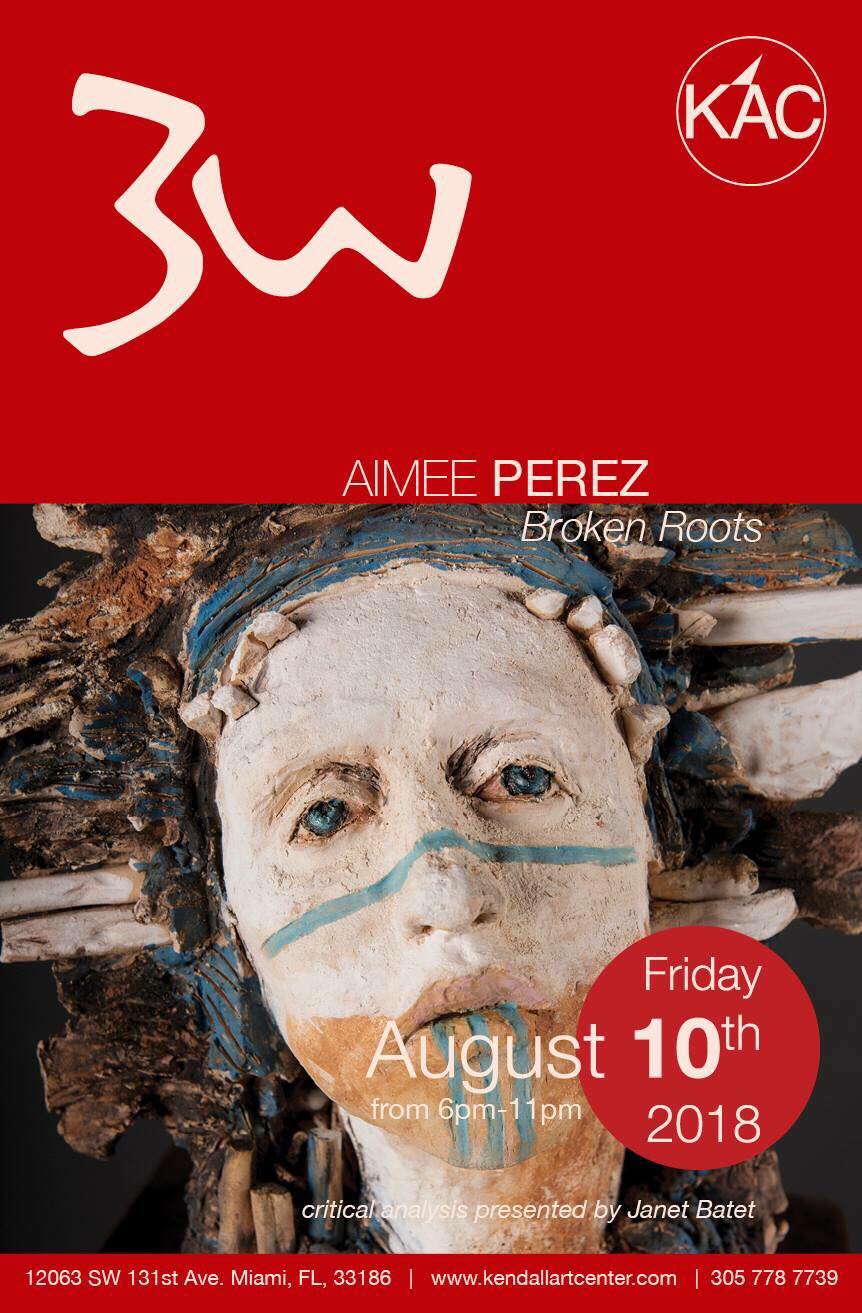

Fascinated by the artisanal work of women in traditional communitiesthat the artist encountered in her multiple travels to Peru, Aimee Perez (La Habana, 1955) undertakes a journey of revision and reformulation of her own work that echoes pivotal questions about life, ecology, gender and art.

For this purpose, Aimee focuses on two of the earliest traditional practices associated with women: weaving and pottery.

Intus, 2018, as its name indicates, is the core of this exhibition. Thetowering installation that evokes a stunning Andeanlandscapeis the result of a lengthily,quasi-mythical process that uses the knot as the primary technique.

Present in several of the pieces, the knot -as a pristine weaving technique devoid of any other tool than the merehands- puts the accent in the process and, consequently, in time. Embodying the natural cycles that dictate the harvest and existence itself, time is directly associated with the cultural preservation oftraditional preliterate cultures that rely on oral lore for the transmission and preservation of their culture and ultimate survival.

The artist is directly inspired by theQuipuwhat in Quechua means knot. This recording device used in Andean civilizations combines knots and colors in a binary system that generates a semasiographic language. While the binary system is directly associated with accounting, the bright red, white, green and yellow colorsas well as the type of fiber (vicuña, alpaca, llama, guanaco, deer and vizcachafibers) used in the quipus seem to enclose a hidden narrative language still today to be decipher.

Closely linked toIntus,Las hilanderas (The Spinners), La tejedora (The Weaver),Nudos de familia (Family Knots), andYo, Tierra (I, Earth) (all of them dated 2018)refer to the essential role of women as a sacred figure in the preservation and transmission of the culture and specifically the figure of the Mamakuna.

The Mamakuna or “virgins of the Sun”were female priest worshipping the Inti(Incan sun god)cult. Trained in religion, spinning and weaving, as well as the preparation of food and the brewing of chicha(sacred maize beer), theylived in segregated communities.

Made ofclay and fiber, Yo, Tierrais a tribute to women as fundamental core holding culture alive. The female figure, devoid of hands and in the act of birth, recalls ancient votive figures where women embodied fertility and life.

Inspired by the urpus (aryballo or storage jar in Quechua) -one of the most distinctive Inca ceramic forms used for the production, storage, and transportation of chicha, La Tejedorais the portrait of a graceful Mamakuna. The eyes captivated in the distance while the hands deliver the unrelentingdaily work.

The vessel as a container for food and ritual–body and soul- is an essential cornerstone in this show. The direct imprint of the hands over the nude clay that might use different natural colors (chocolate, white and peach) (see Nudos de familia) becomes communion with Earth: religare.

In this sense, highlights El Crisol(Melting Pot, 2018) where the inverted vessel represents the giving mother Earth.

Broken Roots isa state of alert about the pressing environmental problems facing our planet, making us aware of ourrole as an integral and active part of that cosmos in crisis. That is the main idea behind pieces like Still Waters(2017), Diary of Fall, Invierno (Winter) and (both 2018) where the artistputs to hand millenarian legends that become at once omen and sentence.

The exhibition is also a reflection on the alienation and fetishism of modern art. The pieces presented in Broken Roots seem to echo Adorno’sand Horkheimer statement related to: “Myth is already enlightenment, and enlightenment reverts to mythology.”

The careful selection of the titles brings upundeferrableassociations that act asunderlying threads unifyingthis exhibition. On one hand, the references to Pre-Colombian and Greek myths highlight the points of contact and immanence between cultures while the citations to iconic masterpieces of the Art History aim to restore the broken harmony between Fine arts and Traditional arts, autonomous and pre-autonomousart.

Broken Roots is that, a labyrinth and a thread in our perennial quest for the restitution of faith or, as Borges claims, a moment of mere and simple happiness.

Janet Batet